From firsthand experience, these are six broad problems with walkability in Seoul that affect all pedestrians, not only the mobility-challenged:

1. Super-wide streets

2. Driver attitudes

3. High-rise apartment complexes

4. Inconsistent sidewalk quality

5. Poor pedestrian access to important public places

6. Land use segregation

Super-wide streets:

Every city contains wide streets to funnel copious amounts of cross-town traffic away from smaller roads, but Seoul takes this idea to its logical extreme. Arterial roads contain anywhere between four and eight traffic lanes in each direction. Crosswalks are few and far-between, and traffic signal cycles may stretch past five minutes. Some streets further limit path choice to pedestrian overpasses (보도육교) or underground walkways (지하보도).

Every city contains wide streets to funnel copious amounts of cross-town traffic away from smaller roads, but Seoul takes this idea to its logical extreme. Arterial roads contain anywhere between four and eight traffic lanes in each direction. Crosswalks are few and far-between, and traffic signal cycles may stretch past five minutes. Some streets further limit path choice to pedestrian overpasses (보도육교) or underground walkways (지하보도).

The sheer dimensions of these streets make it tough for anyone who walks slower than a healthy adult to cross within the limited signal times. Having many lanes available also prompts drivers to treat these streets as expressways and drive faster. For those less agile and less visible to drivers (particularly small children and wheelchair users), wide streets pose a greater threat of collision with a car or scooter.

The sheer dimensions of these streets make it tough for anyone who walks slower than a healthy adult to cross within the limited signal times. Having many lanes available also prompts drivers to treat these streets as expressways and drive faster. For those less agile and less visible to drivers (particularly small children and wheelchair users), wide streets pose a greater threat of collision with a car or scooter.

The lack of crosswalks means longer walking journeys to reach a safe crossing point. Sometimes the only available crossing point is an overpass or underground walkway that involves stairs or other potential injury points. Ascending and descending four flights of stairs in hot, humid summer weather or the cold rain/sleet/snow of winter takes stamina, sure footing, and time.

The lack of crosswalks means longer walking journeys to reach a safe crossing point. Sometimes the only available crossing point is an overpass or underground walkway that involves stairs or other potential injury points. Ascending and descending four flights of stairs in hot, humid summer weather or the cold rain/sleet/snow of winter takes stamina, sure footing, and time.

At best, wide arterial roads severely limit path choice for non-drivers across much of the city, making the average walking trip longer and more physically demanding. At their worst, they pose millions of injury risks to pedestrians, young and old.

How did things get this way?

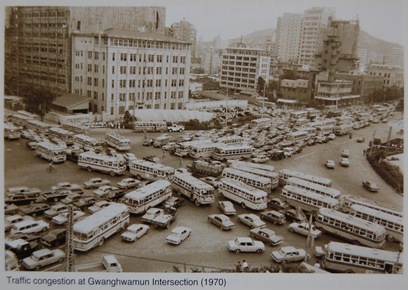

There's no single explanation for why Seoul contains so many super-wide arterial roads. It's sheer size and population generates huge demand for automobile roads, though this is tempered by the scarcity of parking. Many of these wide roads were established as Korea entered an industrial boom, a time when large, modern infrastructure symbolized progress and a better life. Even the unwieldy pedestrian overpasses and underground walkways were welcomed with civic pride as pragmatic solutions to increasing traffic fatalities on the automobile-dominated streets. The result was a planning culture that treated pedestrians as yet another obstacle in the path of automobile efficiency.

There's no single explanation for why Seoul contains so many super-wide arterial roads. It's sheer size and population generates huge demand for automobile roads, though this is tempered by the scarcity of parking. Many of these wide roads were established as Korea entered an industrial boom, a time when large, modern infrastructure symbolized progress and a better life. Even the unwieldy pedestrian overpasses and underground walkways were welcomed with civic pride as pragmatic solutions to increasing traffic fatalities on the automobile-dominated streets. The result was a planning culture that treated pedestrians as yet another obstacle in the path of automobile efficiency.

It would not be fair to single out Seoul's planners for having taken this approach. Nearly every other city in the world has gone through a similar period of road expansion at the expense of the pedestrian environment, and many continue to do so. Seoul went through this period of expansion at a time when large swaths of land were being rebuilt from war damage or newly developed to accommodate refugee influx (especially south of the river). I think Koreans are particularly quick to assimilate foreign technology and organizational techniques, often taking such ideas to their logical extreme. Much of modern Seoul was a tabula rasa, primed to adapt the latest planning techniques from Western cities, yet ignorant of the backlash that massive infrastructure projects had already prompted in these cities. It's only recently that awareness has caught up.

It is also unfair to universally proclaim wide arterial roads an absolute evil. When compared with the alternatives (elevated highways, inadequate access to transit-neglected parts of the city) wide roads are a relatively flexible way of handling transportation load. They can later be modified to include rapid transit bus lanes, converted to boulevards with full-featured parks in the middle, narrowed to accommodate wider sidewalks, etc. A hierarchy of road size and use is also desirable in any large city, making it easier to navigate and creating variety in the cityscape.